Navigating the Climate Crisis: A Conversation with Andrew Boyd, Author of I Want a Better Catastrophe

“The climate crisis is not a problem we know how to ‘fix’ in some simple linear way. Rather, it is a complex predicament we must learn to navigate as we attempt remedies. Because many opposite things about it are true at the same time: Yes, it’s probably too late to stay under 1.5°C, but it’s also never too late – no matter how hot it gets – to act in defense of people and the planet.” – Andrew Boyd

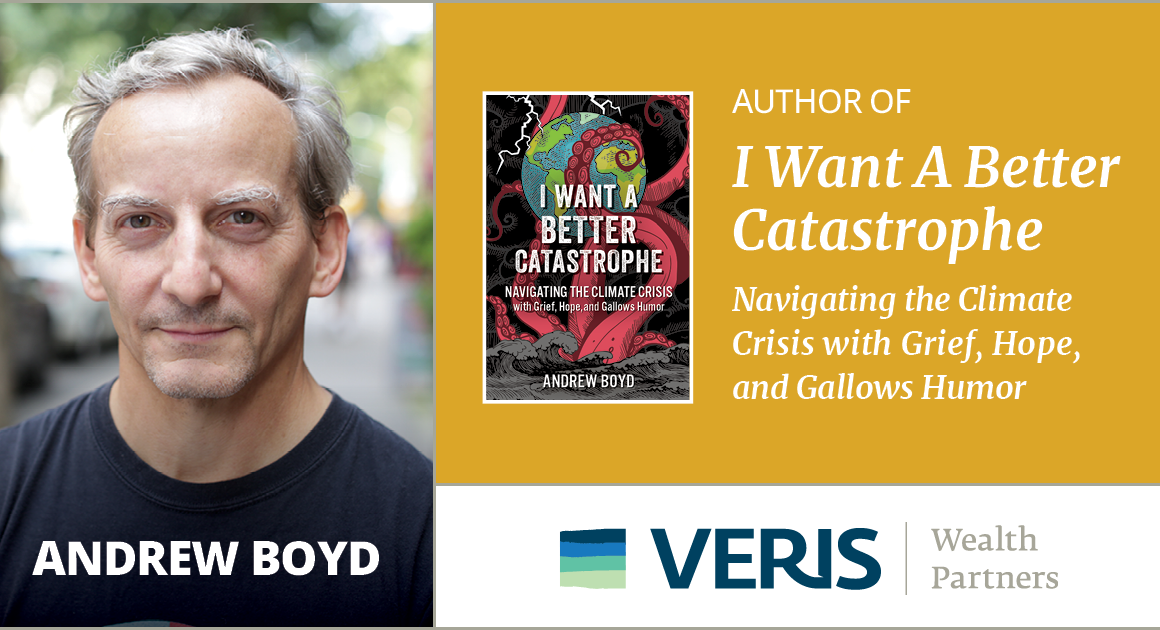

Andrew Boyd, author and co-creator of the Climate Clock and the Climate Ribbon projects, has been a social and environmental activist for over four decades. His latest book is I Want a Better Catastrophe: Navigating the Climate Crisis with Grief, Hope and Gallows Humor. Veris’ Partner and Senior Wealth Manager Nicole Davis sat down with Boyd for a conversation about the realities of climate change, and his perspective on how we can process our feelings of climate grief and do more to fight for the best possible future for all of humanity.

Nicole Davis: For those who haven’t yet had the opportunity to read the book, what does it mean to “want a better catastrophe”?

Andrew Boyd: We have missed many of our key targets to keep warming below 1.5°C. Carbon Action Tracker projects that we are currently on track for 2.7℃. All the terrible impacts we’re living through in this hellish summer of 2023 are happening when we are “only” at 1.2°C of warming. Imagine what the world will be in for at 2.7°C. The book lays out the basic science, follows me on my own journey as I reckon with our situation, and offers tools to help us navigate our climate grieving process and take the kind of action that still matters.

The first step in choosing to live in climate reality is to accept that we are in for some kind of catastrophe. It’s a very difficult step. I think a lot of people are either in a ‘we can still fix this – and keep the world we know’ mode or they’re in doom mode. People switch from one to the other. The book invites you into a mindset of ‘we’re in for catastrophe – so what is the best catastrophe that is still available to us?’ And then guides readers towards ways we can train ourselves philosophically, morally, and spiritually to work towards that better catastrophe.

I interviewed a lot of amazing people for the book who all acknowledge that we’re in for a rough ride, and shared what they think is “better” about the catastrophe they are working towards.

Gopal Dayaneni, a leading voice of the climate justice movement, told me that the question we should be focused on is, how do we distribute the coming suffering most equitably? For him, a better catastrophe will be achieved by looking at our situation through a lens of justice and paying attention to how these impacts are going to roll unequally across our extremely unjust society. He encourages us to design solutions with the most impacted people foremost in mind and approach each moment in the crisis as a contest of power between people- and Earth-friendly solutions vs. “solutions” that favor extractive capital.

Another interviewee, healer and community organizer adrienne maree brown, acknowledges that we’re in for a hard fall and asks us to consider the question: how can we fall in a way that protects the most vulnerable people and places we love. She offers this beautiful image, suggesting we fall as though we are cradling a child on our chest.

The book is a rough awakening, but takes an oddly positive, hopeful, and resilient approach, asking us to do all that we can to achieve the best catastrophe that’s still available to us.

Nicole Davis: What has been the lasting impact – on either your perspective or behavior – of these meetings? How did those conversations change you?

Andrew Boyd: I tracked down eight leading climate thinkers, asking them questions like: How do you hope? What is still worth doing? How can we prepare ourselves — spiritually, emotionally, and strategically — for what is to come?

Celebrated climate activist Tim DeChristopher helped me understand how hope can still work even though we already know things are going to get worse. Hope, he said, is not the likelihood of getting a good outcome, but rather “the will to hold onto our values in the face of difficulty.” That more resilient kind of hope seems a better fit for our challenging 21st Century. This kind of hope is not a mood or lottery ticket; this is hope as a verb, hope as an ethic.

I had a beautiful conversation with Robin Wall Kimmerer by a fire in a cabin in Adirondack State Park. She is the botanist, professor, and enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, who authored the bestselling novel Braiding Sweetgrass, which twins scientific knowledge and Indigenous wisdom. She thinks of plants as our elders and our teachers, making the half joke/half truth that plant life figured out how to have a solar powered economy half a billion years ago – and there’s much we can learn from them. She noted how Indigenous worldviews tend to imbue the natural world with soul, or ‘animacy’, while the Western, scientific worldview strips that away, philosophically setting up capitalism to reduce everything to numbers, property, and commodities, and extract what it wants from a natural world shorn of its magic, presence, and agency.

I met with Joanna Macy, the beloved eco-philosopher and Buddhist practitioner in her Berkeley apartment over tea and cucumbers. She was 90 at the time, and I think she’s as close to a saint as anyone I’ve met. We don’t get to know, she said, whether we are hospice workers of a dying world or midwives helping to birth a new one, but even without knowing, we must still act in service, with loving kindness to ourselves, to our fellow humans, and to all living things.

“Yes, we’re all in this together, but also, no, we’re not. Because a lot of the folks who are suffering the worst climate impacts have done the least to cause the problem. We might all be in the same storm, but we’re in very different boats. So, rather than avoiding these contradictions…the book helps us face them, and find our own path through them. And do that without falling into despair on the one hand, or some kind of false hyper-optimism on the other.”

Nicole Davis: What is one major lesson that you hope readers take away from the book?

Andrew Boyd: A professor of climate science and communication told me that what she most loves about this book is that it allows her to feel all the feelings she has around climate change both good and bad. The book says to readers: it’s okay to have hope one day and hopelessness the next. It’s okay to be working on solutions while knowing that simply living in this civilization makes you part of the problem. It’s all part of the fabric of our situation. So, instead of being paralyzed by these seeming hypocrisies, the book says, embrace the paradoxes, laugh darkly about it, and keep doing all the good you can still do.

Because the climate crisis is not a problem we know how to “fix” in some simple linear way. Rather, it is a complex predicament we must learn to navigate as we attempt remedies. Because many opposite things about it are true at the same time: Yes, it’s probably too late to stay under 1.5°C, but it’s also never too late – no matter how hot it gets – to act in defense of people and the planet. Yes, we’re all in this together, but also, no, we’re not. Because a lot of the folks who are suffering the worst climate impacts have done the least to cause the problem. We might all be in the same storm, but we’re in very different boats.

So, rather than avoiding these contradictions – just because they sometimes feel overwhelming, and complex, and painful, and heartbreaking – the book helps us face them, and find our own path through them. And do that without falling into despair on the one hand, or some kind of false hyper-optimism on the other. To straddle this in-between, the book offers up some mini-philosophies like “tragic optimism” and “can-do pessimism,” giving you permission to, say, have a sour take on how things are gonna play out while still doing all the good that you can. Just don’t become a misanthrope. Stay compassionate. We all need to find our own way of not giving up.

Nicole Davis: What is an action that you hope readers will take after reading?

Andrew Boyd: Despite our dire circumstances, there’s so much good that can still be done, and that must be done.

First, let’s distinguish between individual actions and systemic actions. Even though the very notion of a personal “carbon footprint” was invented in 2004 by PR firm Oglivy & Mather hired by British Petroleum to find ways to shift the onus off of Big Oil and onto individuals, I still think taking individual action is necessary and important. We should recycle and bike more. We should fly less. We should try to switch towards a plant-based diet. We should do everything we can as individuals, but given the scale of the crisis, individual actions alone are woefully insufficient.

So, we must also find a way to use the tools of democracy to tackle the systemic causes of our climate crisis. The book recommends a number of such approaches including an immediate moratorium on new fossil fuel infrastructure and — noting how over $400B tax dollars are given to the global fossil fuel industry every year, underwriting everything from coal plants to new highways — an end to subsidies to the fossil fuel industry.

While we have to be careful of the many false solutions — “clean” coal, carbon offsets, etc. — out there, we are witnessing a flourishing of real ones that we need to get to scale. The solutions page on the book’s website lists a host of things you can do and efforts to get involved in. Project Drawdown has a ranked list of the 100 most impactful solutions for surviving our climate crunch and achieving a just and livable world. Getting involved can also be good for your mental health. As one of my interviewees said, “taking action is my coping – and hoping – mechanism.”

If you’re in the responsible investment world, there’s much you can do: shareholder activism is on the rise, and the Fossil Fuel Divestment movement, having already racked up over $40T in divestment commitments, has a renewed focus on pension funds.

My current project, the Climate Clock is a global effort to get all climate stakeholders to #ActInTime on key solutions. Bill McKibben describes the climate crisis as a “timed test.” If we win later, we lose. Greta Thunberg and Vanessa Nakate, in an open letter to global media on the eve of COP26, declared, “If your story does not include the notion of a ticking clock, you are not telling the full climate story.” The Climate Clock is that clock.

The clock counts down the time remaining to prevent global warming from rising above 1.5°C. It also tracks our real time progress on key climate solution pathways, including renewable energy adoption, fossil fuel divestment, Indigenous land sovereignty, gender parity, regenerative agriculture, and more. As we say, we have “one deadline, but many lifelines.”

One absolutely essential way the responsible investment community can help is with financial support. I like to joke that we’re an “Internet-of-Things start-up hiding inside a global climate justice campaign.” In any case, there’s nothing quite like Climate Clock out there, and it takes a lot to run the whole project, so if anyone out there feels moved to organize your networks to support this critical effort, I can’t tell you how happy (and less stressed) that would make me. And, honestly, it’s hard to imagine a better ROI for our planet and people.

For more information, contact Andrew Boyd at andrew@climateclock.world or visit www.bettercatastrophe.com where you can find his favorite highlights from the book or sign up for his email newsletter.

Nicole Davis is a Partner and Senior Wealth Manager at Veris Wealth Partners.